Has A Witch Spirit Taken Over Your Soul?

The issue, then, is whether a witch person, or witch host would always know he or she had a witch spirit. The Mende disagree on this point, and so do the anthropologists. Some say that when a witch enters a village, it is like a powerful sound in a room filled with tuning forks. Or let’s use a Mende proverb: Hinda a wa hinda. ‘Something brings something,’ or, even better, ‘Like brings out like.’ In the Midwest, they might say, ‘If you plant corn, you get corn,’ something like that. Anyway, some forks respond to the frequency, others don’t, and those responding can ‘feel’ the frequency—they know they are witches, even though they will always deny it.

But others say that often a witch host sees only malice, chaos, destruction, and evil all around him. As time goes on, he senses that the evil seems always to be linked to him. Then, perhaps he has a dream, or is skillfully questioned by a looking-around man or a witchfinder. Suddenly the witch host realizes that the darkness he always so quickly saw in others is really only his own dark powers reflected in the looking glasses of their innocent hearts. He discovers that the evil he had always ascribed to human nature is really the fruit of his own wicked labors. He planted seeds, and now the harvest has come in. His life is filled with evil people, because they are his converts, members of his coven. In one horrible instant, he sees that he is the cause of much of the despair, destruction, and evil in his life. He may have convinced himself that he was only using bad medicine to protect himself—so-called defensive medicines, or counter-swears—but before long, he discovers that he has a witch spirit, and the witch-spirit has gradually … taken over.

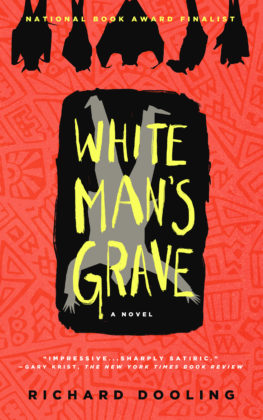

Excerpted from White Man’s Grave, a novel by Richard Dooling