A Brush With Death and a First Novel

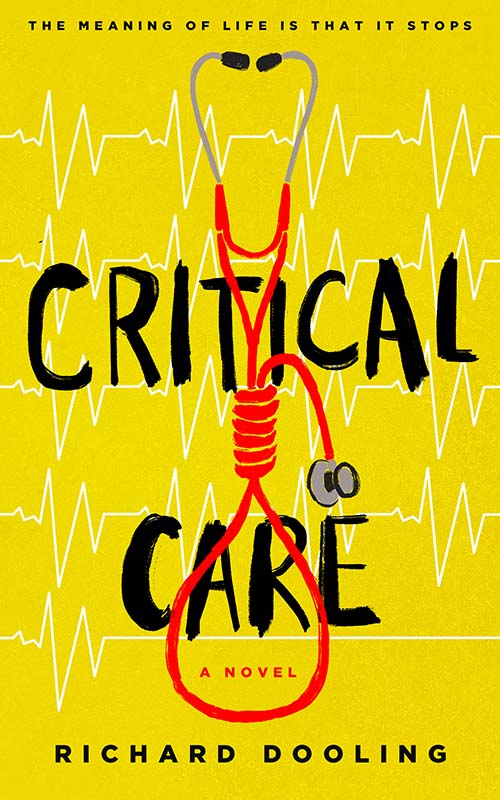

Critical Care, by Richard Dooling

This commentary originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal, “A Brush With Death and a First Novel,” by Richard Dooling.

I was 34 in July 1988—a lawyer living in St. Louis. I was at my desk, leaning back in my swivel chair, hands folded on top of my head, when I felt a rough spot on my scalp. Probably that old scar I got running under the swing set when I was a kid, I thought.

A few days later I was sitting across the table from an oncologist who told my wife, Kristy, and me that I had melanoma of the scalp and an 8% chance of living five years. We had a son and a daughter, both under 2.

“Actually it’s probably less than 8%,” the doctor said as he showed me a bar graph from a recent study. “We see satellite lesions, meaning the cancer has probably already spread.”

A week later, a surgeon put me under and scalped me. The doctors sent the lesion to three different experts who would get back to us in a few weeks. For almost a month, I woke up every night at 3 a.m. and felt cancer spreading through my blood, bones and lymph nodes. I figured my life insurance would last Kristy and the children a year or two, but then what? I tried to think of unmarried friends who might be willing to take my place and provide for my family after my death.

Desperate, irrational thoughts, to be sure. I also thought of Anthony Burgess, who, in 1959 in his early 40s, was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. The doctors gave him one year to live. Burgess wrote five novels, including “A Clockwork Orange,” in a little over a year to provide for his wife after his death, which turned out to come more than 30 years later, when he was 76.

Burgess was already a published novelist at the time of his brush with the beyond. All I had was an early unfinished draft of my first novel, “Critical Care,” a medical satire I’d written years before while working night shifts in intensive-care units as a respiratory therapist. I had seen dozens of people die in the hospital and had mastered the indelicate art of ICU gallows humor. The novel seemed less funny now that the melanoma had shown me what dying feels like to the patient.

I poured most of those feelings into a character I named Stella Stanley, a crusty ICU nurse played by Helen Mirren in the 1997 movie adaptation. Stella was a breast-cancer survivor who, like me, had been told that death was coming soon. Memory is merciful, and psychic trauma tends to cover its tracks, as if the ghost in our machine is an editor saying, “Well we don’t need to remember how bad that was.” But thanks to Stella I recall almost exactly what I thought about while waiting for test results.

“The word ‘malignant’ wound itself like a tentacle around her throat. . . . Eternity assumed abbreviated, five-year proportions, and seconds became large rooms for Stella to sit in and realize that she was dying. . . . Her first day home from the hospital . . . her evening walk lasted about six months. Clouds sailed through vistas of color, and all of nature held itself in a trance for her to look at for the first and last time.”

Sure, I was trying to be profound, but I also wanted a book advance. I took a one-month leave of absence from lawyering and finished a complete draft. The melanoma experts came back with good news. The cancer hadn’t spread—yet. My odds of living five years soared to 50%. Even odds! I took them.

Mr. Dooling is a novelist and retired lawyer.