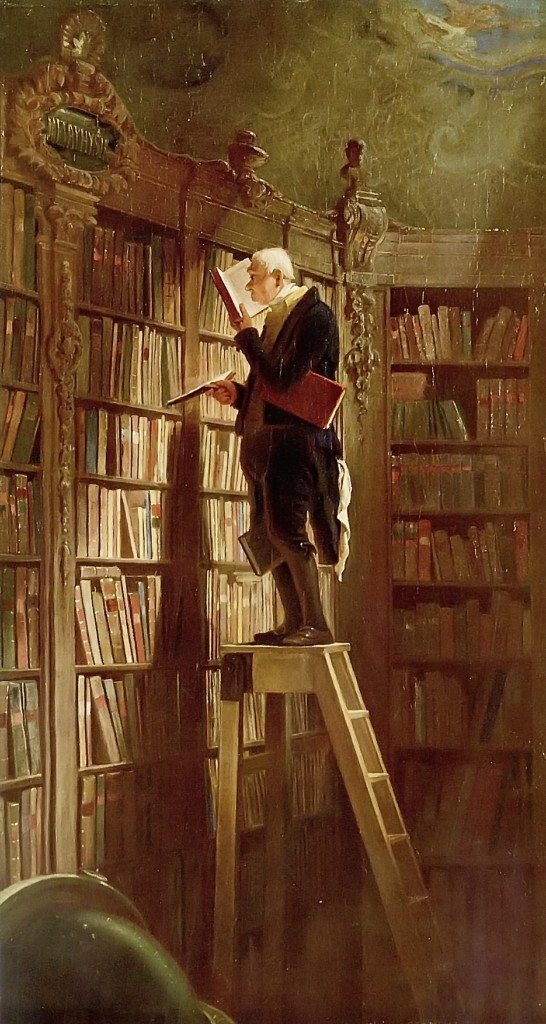

I spent my undergrad years painting dorm rooms to pay my tuition and never once allowed schooling to get in the way of my education. I graduated from St. Louis University in 1976 and decided it was time to actually read all of the books that I never had time to read while I was a working student. I lined the walls of a one-bedroom apartment in midtown Omaha with concrete-block-and-board shelves and soon amassed a formidable library of trade paperback books.

For years, I worked day jobs and spent the rest of my time reading and writing. Maybe I was testing the truth of Augustine Birrell’s claim that any ordinary man can surround himself with two thousand books and be happy for the rest of his life.

Happiness or no, in 1980, I decided to “see the world.” I read a fantastic book called The Art & Adventure Of Traveling Cheaply, by Rick Berg. Berg’s book could have been subtitled: Travel Light. Everything should fit in one medium-sized backpack, including your sleeping bag and ground cloth, one long sleeve shirt, one T-shirt, one extra pair of socks, underwear optional. Carry-on only! Don’t even think about checking it. For the next year or so it’s all you have in the world.

Traveling Cheaply offered excellent advice, especially about traveling in the Third World. How to haggle with officials at remote border crossings, how to change money when there’s no bank, how to purify water with laundry bleach. True to his word and his spartan rigor, Rick Berg told his reader to leave the travel book at home. Berg’s book was not a Baedeker or a Lonely Planet guide to be consulted during a two-week trip to Morocco, it was a manifesto to be read before leaving for months, or years. If memory serves, the epigraph at the start of Traveling Cheaply is Tolkien’s famous observation: “Not all those who wander are lost.”

I saved some money and collected the gear I would need for a year abroad. Then, before I left for Africa, I made one huge mistake: I gave away all of my books. A close friend of mine warned me that it was wanton folly to give away one’s personal library, but in keeping with the mantra of Traveling Cheaply I intended to purge myself of earthly belongings and wander the world unfettered.

I traveled in Africa and Europe for over a year, and upon return, promptly began reading and collecting books again. Now, almost thirty years later, my family and I live in a four-bedroom house with multiple bookshelves in almost every room. Because I’ve never organized the volumes, they tend to be grouped roughly into the time periods and interests of my life. So if I need a book from, say, the neuroscience phase I went through in the mid-90s while researching my novel Brain Storm, I go to the basement and survey the shelf of brain books. It’s right next to a shelf stuffed with the anthropology books I read while I was researching another novel, White Man’s Grave. These books are often annotated, highlighted, underlined, because I usually have a pen or pencil in hand when I read.

Now comes the sad part. To this day I wander to the basement where most of the books from the 80s and 90s take up the better part of a long wall, looking for, say, Humboldt’s Gift, by Saul Bellow, only to realize after 15 or 20 minutes of searching that Humboldt’s Gift must be one of the books I gave away before heading out to Africa. I’ve never stopped to consider the almost archeological nature of this process, of excavating my past by poking through the books I’ve consumed, until I came across Nathan Schneider’s excellent essay, In Defense of The Memory Theater, where he describes the sensation of searching for a lost book:

What suddenly became most evident were the absences, the missing books I could hazily remember having read and digested, yet which would need referring to again. They had turned, terrifyingly, into phantom limbs.

These days, I spend well over half my time staring into a MacBook, reading or writing, but I have not yet made the leap to digital books, for many of the same reasons Schneider so alertly describes. The ability to make notes, to save and highlight passages, seems clunky at best on the Kindle, and I do not trust any profit-driven corporation and its obsessions with digital rights management. All I can be sure of is that if I break up with Amazon or Apple or Barnes & Noble and Microsoft I have a pretty good idea who will end up with the books. But Nathan Schneider’s essay is also an elegy for books. Let’s not kid ourselves. People who have never collected books, who have never wandered the memory theater looking for a long lost obsession, will have nothing to miss. While reading Schneider’s essay, I was reminded of Nicholson Baker’s Discards published in the New Yorker in 1994. Baker was bemoaning the loss of library card catalogues, because it also meant the loss of the painstaking, handwritten annotations that librarians and scholars had made on the cards.

I’ll await commentary from some young person who will assure me that they can search their digital library in a flash by typing “Humboldt’s Gift” into a search box and poof! There it is, annotations and all. I hope so. I’m just worried about who will “own” my memories five, or thirty, years from now, and whether it will be possible to stroll and excavate the memory theater.

And I sure miss my copy of Traveling Cheaply. Now that would bring back some memories . . . .

Postscript

Almost ten years later, I am a fan of ebooks and Kindle Voyage for several reasons:

- Reading in bed when your spouse is sleeping. The device emits almost no light, so it’s possible to read at three a.m. without incident.

- Notes! See the above complaints about not being able to make notes in the margin, circle things, and put an exclamation point at the top of the page. On Kindle you can highlight passages, leave e-notes for yourself, and even look up words in the dictionary. And when you are done with the book, you can access those notes and highlights at Amazon, download them, print them out for review. Handy.

- A single charge of the device lasts for weeks. Perfect for backcountry camping trips.

- The Kindle Unlimited program. For $10 a month you can read as many books in the program as you like, including books like White Man’s Grave and Critical Care.

That said, I still like to sit by the fire with a cup of tea and a real book.